2025 - Year In Review

Dec 31st, 2025I can’t remember where I saw my first Year in Review. It was probably Google’s, sometime around 2008, back when Google was a big part of the search and internet scene in China, and when I was still a primary school kid running around on summer afternoons, thinking nothing about jobs or life.

Fast forward to 2025, Year in Review is everywhere: Spotify, Instagram, LinkedIn…… even ChatGPT. I expected it to feel awkward, but OpenAI handled it surprisingly well.

I’ve always found retrospectives useful, both for clarity and for growth. So here it is: my reflection on 2025.

Career

This has been the most significant year of my career since 2019–2020. I left Yelp after five years and re-entered the job market during a period dominated by layoffs and hiring freezes. I’ve written a more detailed look back re. this transition in A Walk through Foggy Midsummer Nights - Written at the End of a Job Hunt).

Now after nearly six months into my new role, I can confidently say it was the right decision.

Yelp is a large, stable, and mature organization. In SearchUX Mobile, my work centered around delivering features within a highly optimized and well-defined environment. Execution was the primary focus, while much of the surrounding system complexity was deliberately abstracted behind clear organizational boundaries.

At DuckDuckGo, the Apple team (iOS and macOS combined) is just over 30 people, and the ownership model is fundamentally broader. Feature delivery is inseparable from system design: the same engineers are responsible for instrumentation quality, CI/CD reliability, infrastructure decisions, and long-term maintainability.

When other new joiners talk about what surprised them most, they mentioned project leadership, async workflows, or remote collaboration, but those elements felt familiar to me. They are practices I had already internalized over the past five years. The real shift for me wasn’t how we work, but where decisions get made. Many systems here are still evolving, and fewer decisions come with predefined answers. That ambiguity requires stronger judgment and clearer technical framing, but it also creates space for real impact. This year marked a transition from operating inside established systems to actively shaping them, and that shift has been one of the most meaningful steps in my growth as an engineer.

Learning

My learning this year came in phases.

Interview Prep

The first phase happened during job searching. Returning to interviews forced me to step back into fundamentals: algorithmic problem solving and native iOS development with SwiftUI and UIKit. After years at a large company, much of my day-to-day work had been with internal frameworks built on top of Apple’s APIs. That abstraction is valuable at scale, but it also makes it easy to lose direct contact with the underlying primitives.

Preparing for interviews pushed me to deliberately refresh those foundations. I spent focused time revisiting Swift language changes, native frameworks, and platform conventions by reading documentation, blogs, and WWDC sessions. This paid off not just during interviews, but later when ramping up at a new company: picking up unfamiliar codebases and patterns became noticeably faster.

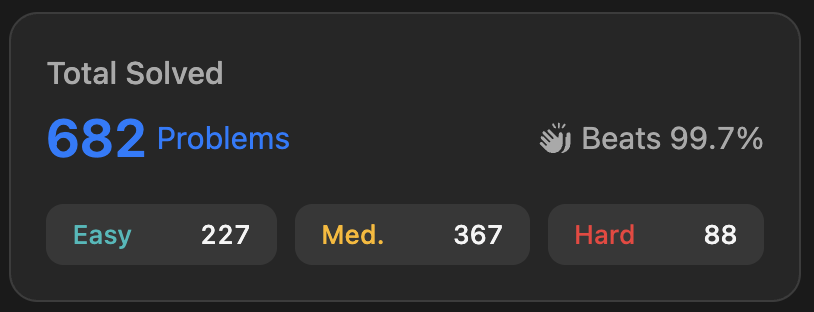

LeetCode was also part of this phase. I have a complicated relationship with it, and I’m not someone who claims to excel at algorithmic puzzles. Still, I find it useful as a form of technical conditioning. I think of it the same way I think about scales in piano or drills in dance: they’re not the performance, but they enable it. Easy-to-medium problems in particular turned out to be a practical way to practice language fluency and newer Swift syntax (especially with Swift 6). I’ve worked through roughly 600 problems so far, and while it’s still hard at times, the returns come quietly.

Ramp-up

The second phase started after joining DuckDuckGo. Although the company is relatively small, the Apple codebase is large and complicated. I invested in building a systematic ramp-up process for myself. Each week, I carved out dedicated time to deeply understand a feature end-to-end: user flows, code paths, abstractions, interactions with other systems, backend APIs, instrumentation, and tests.

I learn with structured “thinking on paper” technique by maintaining private internal notes as if I were writing documentation for each feature. This approach helped me reason more clearly about the system and surfaced opportunities for improvement that wouldn’t have been obvious from task execution alone. Over time, it became a reliable way to both ramp up quickly and generate higher-leverage technical proposals.

Continue Improvement

The third phase is ongoing and overlaps with the second. As the initial ramp-up load eased gradually, I started investing more intentionally in generative AI. With a background in full-stack development and prior exposure to AI coursework, the conceptual foundations weren’t foreign. I used the company’s learning budget to enroll in a GenAI nanodegree and began exploring how these tools intersect with client-side development, including Apple’s Core ML ecosystem.

I don’t view this as a pivot away from client engineering, but I do believe that modern engineers, regardless of their platforms, need to understand generative AI: what it is, where it fits, where it doesn’t, and how it can be responsibly integrated into their domain. For me, that means using AI to amplify judgment and effectiveness, not replace either.

Book

This year, my reading leaned heavily toward utility. The two books I spent the most time with were Cracking the Coding Interview and Designing Data-Intensive Applications. Both were useful, but in a very specific, purpose-driven way.

Somewhat surprisingly, this was my first time reading Cracking the Coding Interview end to end. Going through it brought back vivid memories from my school years practicing Olympiad-style math: problems that start deceptively simple, then ramp up quickly until the gap between “almost there” and “correct” feels enormous. It’s frustrating in familiar ways, but it’s also one of the few places where core algorithmic patterns are explained systematically outside schools.

Designing Data-Intensive Applications is unapologetically backend-focused, and it’s a very demanding read. Still, as a client engineer, I found it surprisingly valuable. Modern iOS and macOS apps aren’t just UI layers. Instead they’re distributed systems in miniature, with persistence, synchronization, APIs, and failure modes. This book helped me step out of a purely UX-centric mindset and think more rigorously about data flow, consistency, and architecture on the client side. It’s not an easy read, but it’s one that reshapes how you think.

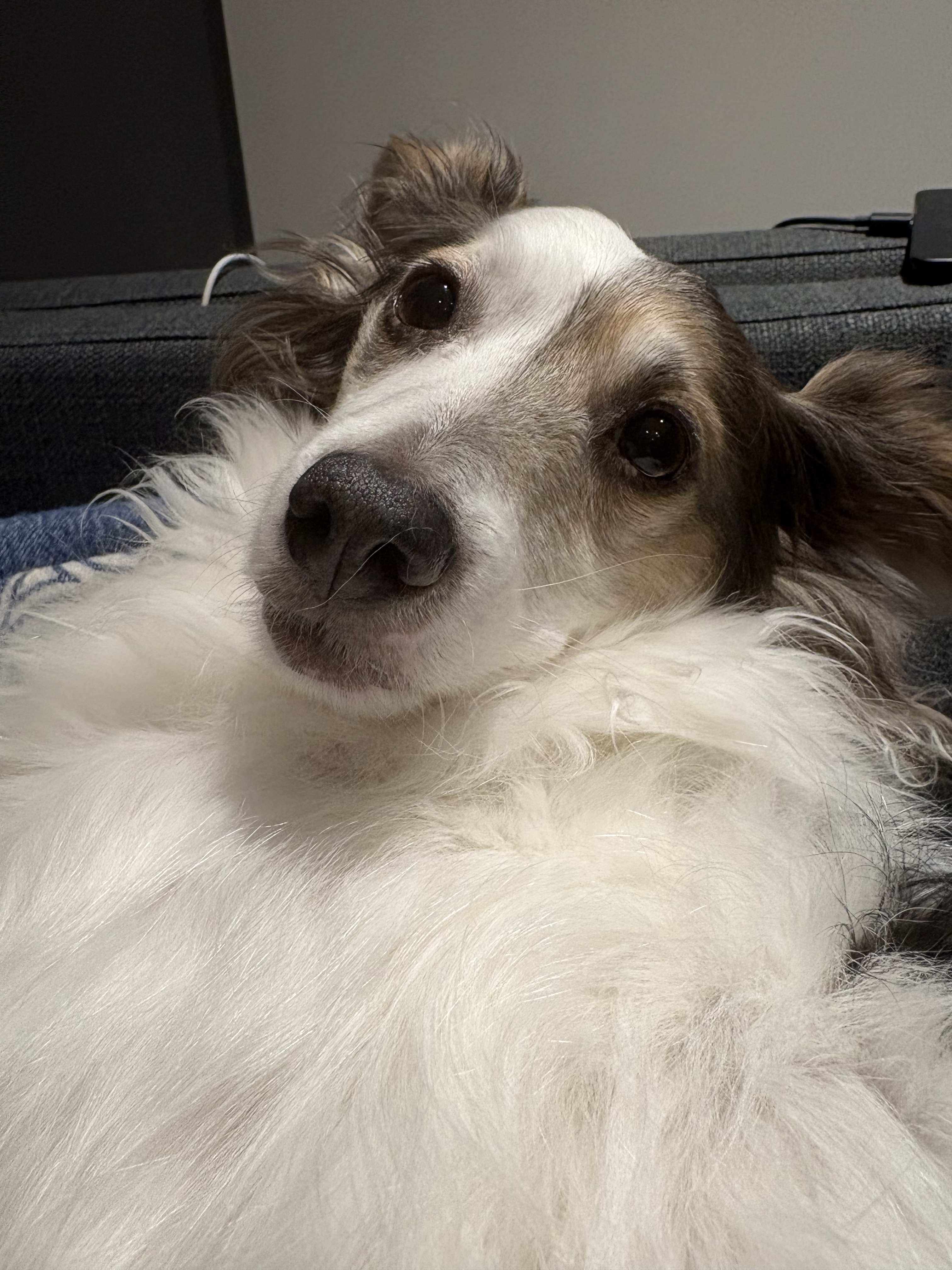

Gourdy

Although this blog is mostly about work and serious things, I can’t end it without mentioning this little boy. He turned 9 this September and officially entered his senior years. It still feels unreal. In my head, I still see the four-year-old pup I first met on a summer day in the Bay Area. Then I remember that I’ve been working in this industry for five years, and that junior engineers now sometimes look to me for guidance, mentorship, or perspective (and that my title is, officially, Senior Software Engineer).

Somewhere along the way, both of us got older. The contrast still catches me off guard. I suspect it always will, and maybe that’s not a bad thing.